We went to Burma (now Myanmar) in 1994. We had signed up for a trip to Thailand with Bolder Adventures, and they called us a few months before departure to say they were putting together a trip led by Lonely Planet author Joe Cummings, Bolder’s Davies Stamm, and Golden Land’s “Mr. William”, and offered us the opportunity to be among the first tourists to be able to go to many parts of Burma. Previously only one week visas were given. Although LP says independent travel is possible, and this comes from Joe Cummings who speaks only a couple of words of Burmese, I would think that logistics would become such an overwhelming task as to make a trip difficult at best. The population is not mobile and the government severely restricts travel by citizens. The only people traveling are those who have a darned good reason, are businesspeople, or tourists. And this is not a lot of people.The trip was fantastic – but not flawless We were a small group of 11, which included a pilot who was one of the first women to fly commercially, a couple from Rhode Island who had spent years studying wildlife in Africa, as well as someone who had been in Burma/Myanmar during WWII.

When we arrived at Bangkok Airport, Thai Airways didn’t have enough seats for all of us, despite confirmed reservations. (This is a theme with Thai Airways; they often bump people to make room for VIPs). Phil had just read an article how a traveler who pleaded to get on a flight within Russia and was assigned the bathroom. With this suggestion, one person in our group was successful in getting a jumpseat, and Davies was given a seat in the cockpit.

Our visit started with a train to Mandalay, and was our first opportunity to interact with Burmese people, many of whom had clearly never seen tourists before. From the moment we arrived, it was clear that Burma hadn’t changed much in the last 100 years – or longer. Its historic isolation has helped them resist westernization.

We began by visiting Mandalay’s temples and shrines, and visited several craft shops, where people carried on the traditions of weaving, ceramics, puppet making and creating gold leaf for temples. From Mandalay we traveled to a monastery in the Sagaing Hills, where there was a chance to interact with the young boys who were studying to become monks and go to a bustling flower market. In Burma, as in Thailand, monks of all ages shave their heads and go to the village twice a day with rice bowls, which are filled by others to earn merit in their next lives.

From there, we took a passenger ferry down the Mekong River to Pagan. This was one of the highlights of the trip. We found the Burmese to be open and welcoming, yet quite shy. The Burmese people were eager to meet and speak with Americans. Women offered Susan white paste for her face, which women throughout Burma wear as a sun block, and insisted on carefully applying it for her. All along the riverbanks we saw small villages with cattle-drawn carts as people went about their lives, washing in the river, gathering water and tending their homes.

Pagan is the area where Burmese people of means and royalty historically built their tombs, shaped like bells and with dozens of temples. The tombs are spread out over dozens of square miles, as far as the eye can see, and were particularly magnificent a sunset. Burma is a deeply religious country, with a fascinating mix of animism (thru “nats”, impish demigods) and Therevada Buddhism.

From Pagan, we visited some hill tribes outside of Kalaw, which Phil dubbed a “death march”, as we climbed the hills slowly in the hot sun. We were put to shame by women in flip-flops carrying lumber, passing us at a quick clip. Throughout, we saw people in their tribal clothes, working the fields, and waving at the funny looking white people. Upon arrival, at least two dozen children came running out to stare at us and to escort us into what appeared to be a community space. Susan felt compelled to show them her magic trick where she pulls a string through her neck – the photos of the children’s faces show their glee and wonder.

We also visited Pindaya caves, which are filled with thousands of Buddhas, and Inle Lake, where we watched a young boy ride his water buffalo through the waters. The people of Inle Lake are known for paddling their boats while standing on one leg; we didn’t attempt this.

As our bus traveled towards our next destination, we saw a rice festival, and were waved over by the participants to come and join the dancing. They then invited us to a local wedding, which we were certainly not dressed for, but the dancers insisted it would bring luck to the bride and groom. This was so typical of the warmth and welcoming people that we encountered on our trip, in spite of the language barriers. Due to the British occupation, many older Burmese speak English, as do some 20-somethings, but for the most part, smiles and hand gestures were all that was needed.

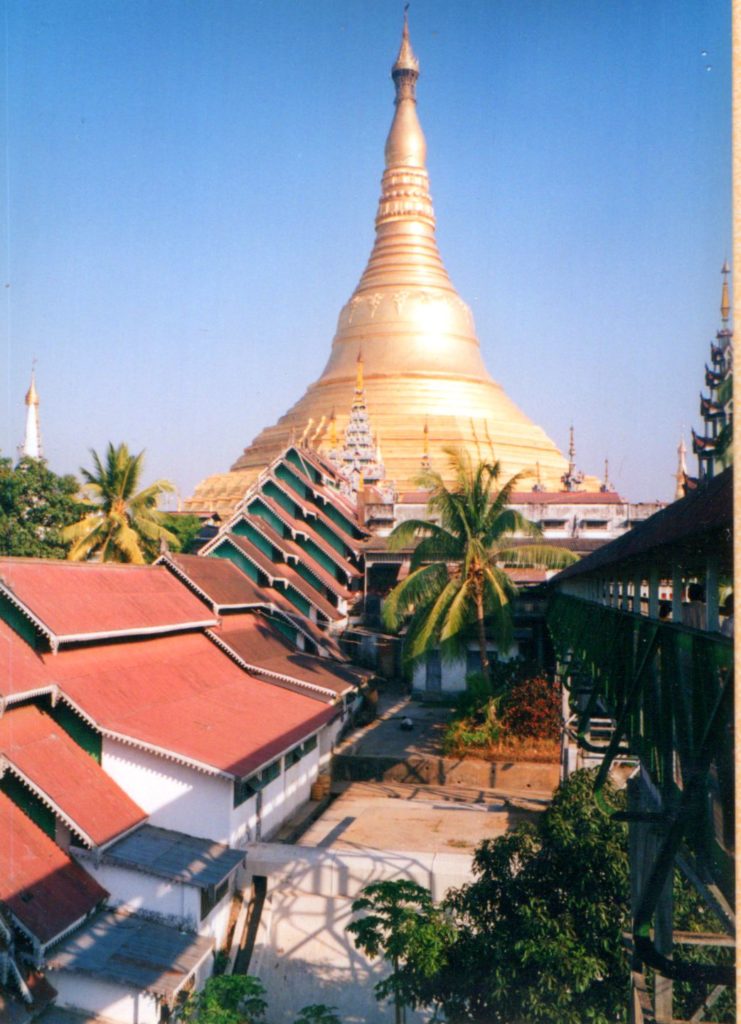

Our final stop was Yangon, where we spent several hours at the amazing Shwemawdaw and Shwedagon Pagodas. It rivals the Temples in Bangkok and was thronged with families and worshippers.

As a side note, we became good friends with the couple from Rhode Island, who on our first visit to them took us out on their canoes, starting what would become a major recreational focus for us in the years to come.

This trip occurred during a short “golden” period where travel within Burma was encouraged, before the international boycott, before Aung San Suu Kyi was freed from house arrest and ascended to power, before the government’s atrocities against the Rohingya people, and long before Suu Kyi’s subsequent arrest.

Although SLORC, the Burmese version of East Germany’s Stasi, was deeply feared, we didn’t encounter them – that we knew of. Our guides were always careful to say “The Lady” rather than “Aung San Suu Kyi, who was under house arrest. We had to keep reminding ourselves that we were only seeing the surface of this country, which is under the iron fist of SLORC.

At one point, Phil met the parents of an MIT student that he was in touch with. They offered Phil a group of older coins for “whatever Phil wanted to pay” (in US$). They stressed that he keep the meeting and the coins an absolute secret, and not carry their names or addresses on any documents in his possession.

Hotels: Most Burmese hotels were above our personal minimum standards, although one had no running water – and had rats. We were not delighted with the Burmese food, which is often flavored with nagapi, a pungent fish paste, and tended to be very oily.